Jen Couch

Around 150,000 refugees live in protracted refugee situations along the Thai Burma border where they are contained in isolated camps. Having spent much or all of their lives in confinement, young people ambitiously progress through the basic camp education system only to find themselves with few opportunities to further their studies.

One way of addressing this need for education is the diploma offered through the Australian Catholic University (ACU), the first tertiary institution to offer accredited university education to refugees and migrants in protracted refugee situations. The program is funded solely by ACU as part of its community engagement program. ACU works in partnership with community-based organisations in the refugee camps to identify potential students with the commitment to remain on the border. In addition, a Memorandum of Understanding between ACU and the students asks them to devote at least two years of their time after graduating to the refugee or migrant community. Through this process the community requests subject topics/themes, and subjects subsequently reflect the needs and priorities of the refugee community.

In this post I reflect on the delivery of one of the subjects that I teach in the program, titled ‘adolescent development and wellbeing.’

Taking off my shoes and walking into the wooden house that serves as the ACU classroom for the first time, I was aware of the complexities of the classroom and that I must adapt my teaching – both for myself and my students. While I have engaged extensively with Western theories of youth work, the limitations of this knowledge for understanding non-Western contexts has been evident to me for some time. Little is documented about the experience of adolescence in the non-industrialised world and adolescence is often absent from many development policies.

In teaching on the border I draw upon Raewyn Connell’s work on ‘Southern theory,’ which seeks to respond to the fact that most social theory that informs higher education being produced in, and from the perspective of, the Global North. Despite claims of universality, these Eurocentric theories fail to account for Indigenous voices and knowledge from including youth experiences outside of Western societies.

The Thai-Burma classroom is not a homogenous environment with a common understanding of oppression, but a deeply divided space of different ethnic groups who all have their own experiences of living in and escaping from Burma. It was critical at the start of the class that I constructed a safe space to enable critical and productive dialogue. This space was not intended as a therapeutic intervention, but rather a space of critical emotional praxis – where pedagogical opportunities are created for critical inquiry and where a restoration of humanity, healing and reconciliation can take place. When a classroom is a safe place, and common feelings of vulnerability and empathy emerge, and we can relate our stories, we set up better conditions for new relations.

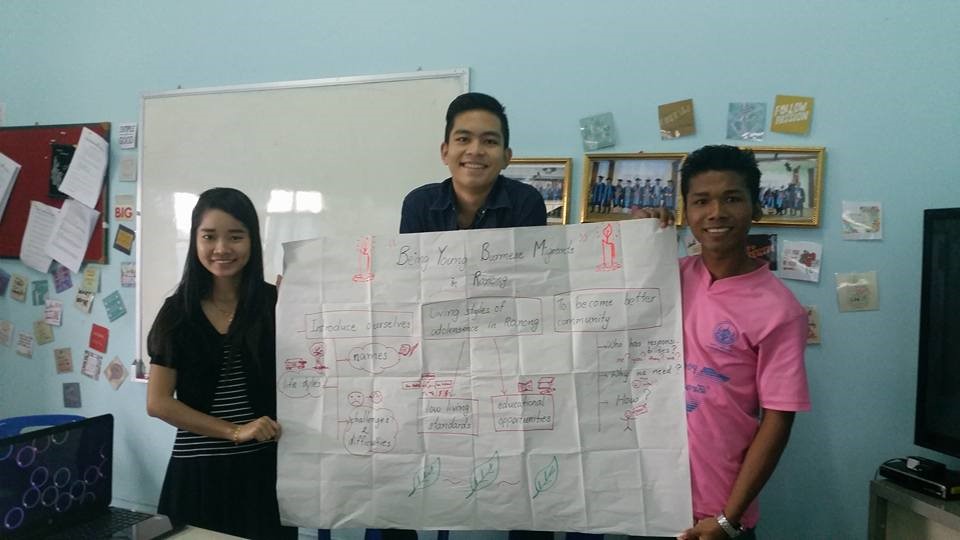

Figure 1. Creating a classroom of dialogue

Sitting in a circle, we begin a process of collectively establishing classroom “expectations”. I remind the students that we all agreed that experience was important knowledge, and that as we draw on our own experiences confidentiality is important. There was some discussion as we translated the concept of confidentiality into Burmese and Kareni – the closest words to confidentiality in Burmese are Liu wak and teb dot the er, which translate to “secret”. Being mindful of the impact of secrecy and silence perpetrated by the Burmese regime, we discussed this more in terms of not “gossiping” outside the classroom, and that “what is said in here stays in here”. One student referred to the Buddhist concepts of sanctuary and refuge as a living space within the class.

My aim from that point on was to create a student–teacher-led classroom process in which we “read from the centre”. To start with I asked the class what music young people like to listen to on the border. Students were keen to tell me about a Burmese band called Iron Cross – the most popular band in Burma. They play Western-style music with Burmese lyrics that first have to be approved by a board of censors. Students all comment that Lay Phyu, the group’s lead singer, is the most admired celebrity in the country because he taunts the military junta at every opportunity.

In class we listened to songs from an album called Power 54. Students told me that it was being sold in shops before the government realised 54 is Aung San Suu Kyi’s street address. Another time, Lay Phyu’s hair was down to his waist and the government told him to cut it. So he shaved his head. And then a military officer asked him to perform at the wedding of his son and Lay Phyu said, “These are not our people”. Using this as a starting point allowed a discussion around young people and rebellion, resistance and disaffection, and on some of the issues that are symbolic of this disaffection – drugs, gangs, suicide and violence.

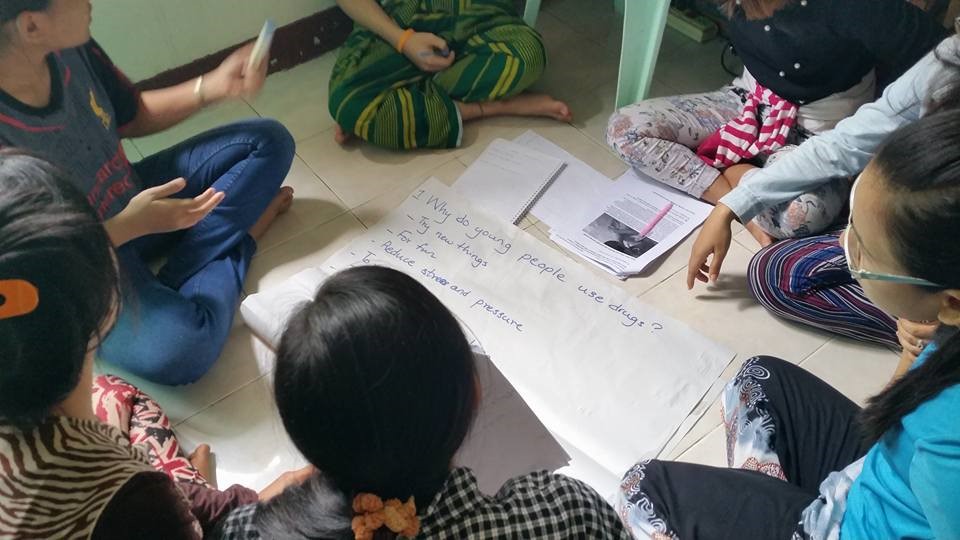

Figure 2: Workshopping the issues for young people on the border

This was how the class started each morning, and when the song concluded I asked the students to summarise the major themes discussed in the lyrics and relate these to the lecture or discussion topics. Students were asked to make connections with their own lives and experiences. Did they have any personal experiences that would support or undermine the situations described in the songs? This created a powerful setting for presenting and reviewing material and making connections between their own experiences and the larger social, economic and political context.

The songs students chose are also important for another reason. Building a classroom community was one of the central features of the critical praxis employed. It has been suggested that such collaborative learning can motivate students, but can it bring about a more socially just world? Students told me that they feel ethnic reconciliation among the Burmese is essential for the future of their country. The creation of this democratic space through such classroom practices was in many ways an act of social justice.

Figure 3: Enacting a democratic space

The Thai-Burma classroom taught me the importance of recognising the validity of non-metropolitan experiences of being young, as well as to challenge the terms in which dominant youth studies theory is currently constituted. In reflecting upon this experience, one conclusion that can be reached is that it is the duty of development educators to understand and enact a decolonised pedagogy that is grounded in theory, possible in practice and shaped by the realities of students’ lives. This does not mean transferring Western development knowledge to the periphery. Rather, such pedagogy should be grounded in the diversity of everyday life and interrogate students experience in the context of power, privilege and oppression to provoke action and dialogue toward humanisation and liberation for all people regardless of location.

Iron Cross: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jgu0UjQDhXs

For a more detailed discussion of the pedagogical aspects of this program see: https://ajal.net.au/on-the-borders-of-pedagogy-implementing-a-critical-pedagogy-for-students-on-the-thai-burma-border/

Jen Couch bio

Jen Couch is a senior lecturer in youth work and international development. She came to ACU in 2005 with a professional background in international community development, youth work and working alongside displaced and marginalised communities particularly in refugee contexts and in South Asia. In particular she has worked with community led organisations and social movements in addressing forced migration and displacement.

Jen is passionate about social resilience and how to strengthen and rebuild following experiences of community upheaval, violence, and trauma. She has published widely in the area of young people, communities and marginalisation and is particularly interested in working in hopeful and positive ways to change social inequalities and exclusion. Jen recently completed the first longitudinal ethnographic study to explore refugee young people and homelessness in Australia.

Her current research is focused on the lived experience of refugee young people during COVID 19.